基础使用

Tutorial

[TOC]

Welcome to the PMP library tutorial!

This tutorial will walk you through your first steps using PMP. After completion, you should be able to build your own mesh processing applications and use PMP for a variety of mesh processing tasks.

Note that this tutorial is not a comprehensive introduction to mesh processing. If that’s what you are looking for, we highly recommend the textbook of Botsch et al. \cite botsch_2010_polygon.

By the way: This is a living document that’s built from the latest version of our sources. If you spot any errors, inaccuracies, or typos, please don’t hesitate to report them using our issue tracker. Your feedback and suggestions are welcome!

Getting Started

Let’s begin by getting the PMP library source code and building the library and its example applications. In the following, I’m assuming you are using a Unix-like operating system such as Linux or macOS. If you are on Windows the steps are the same but the exact commands might be slightly different.

First, clone the repository using git:

git clone --recursive https://github.com/pmp-library/pmp-library.git

\note The --recursive flag above is important to get the third-party libraries required to build PMP.

The next step is to configure the build system using CMake. Create a separate build directory for all the files you’ll generate:

cd pmp-library && mkdir build && cd build

Now run CMake to generate the build files:

cmake ..

This should work out-of-the-box as long as you have recent compiler and standard build tools installed. In case of doubt, see the detailed @ref installation instructions.

By default, CMake will generate Makefiles on Linux and macOS. You can now build the library using

make -j

After watching a few pages of compiler output passing by, you should see something like this:

[ 98%] Built target subdivision

[100%] Linking CXX executable ../mpview

[100%] Built target mpview

Congratulations! You successfully built PMP!

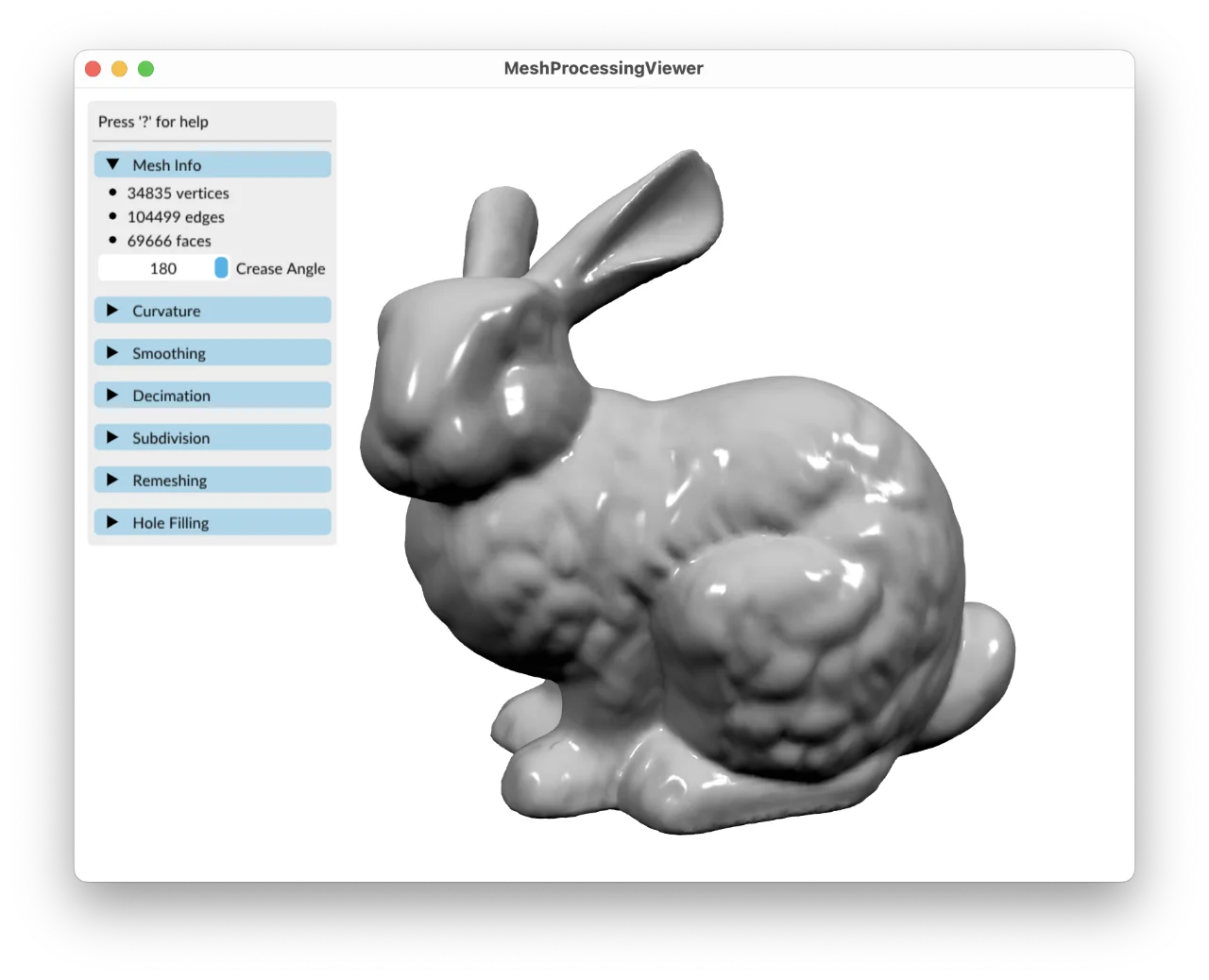

We include a number of example applications that you can to try out. The mpview application provides a simple graphical interface for many of our algorithms. You can give it a try and see what you can do with the famous Stanford bunny:

./mpview ../external/pmp-data/off/bunny.off

You should see a window like this:

If you’re having trouble with one of the steps, please read the detailed @ref installation instructions carefully. You can also head over to our discussions forum and ask for help.

Basic Concepts

Polygon meshes are a fundamental data structure for representing 3D surfaces in computer graphics and geometry processing. A mesh is composed of vertices, edges, and faces:

- Vertices are the individual points defining the shape of the object. Each vertex typically has 3D coordinates $(x,y,z)$ associated with it. In many applications additional properties such as colors or texture coordinates are stored for each vertex.

- Edges are the line segments connecting two vertices. They define the boundary of each face. In a manifold surface mesh, all edges are connected to exactly two faces. In PMP, all meshes are manifold.

- Faces are the polygonal shapes that make up the visible surface of the object. Each face has at least three vertices. Triangles and quads (4 vertices) are the most frequently used faces. PMP supports meshes with general polygonal faces.

We also call those mesh elements.

In order to access and manipulate the mesh, you also need incidence relationships between those elements. The central class for storing and manipulating all that data is pmp::SurfaceMesh. It stores connectivity information based on halfedges, i.e., pairs of directed edges with opposing direction. To be more precise:

- Each vertex stores an outgoing halfedge.

- Each face stores an incident halfedge.

- Each halfedge stores its incident face, its target vertex, and its previous and next halfedges within the face.

The halfedge connectivity is illustrated in the figure below:

In the following, we show the basic usage of pmp::SurfaceMesh by example.

Adding Elements by Hand

The basic usage of pmp::SurfaceMesh is demonstrated in the example below. The program first instantiates a pmp::SurfaceMesh object as well as four vertex handles. These handles, as well as the handles for the other mesh elements Halfedge, Edge and Face basically indices. Four vertices are added to the mesh, as well as four triangular faces composing a tetrahedron. Finally, the number of vertices, edges, and faces is printed to standard output.

\snippet basics.cpp basics

Iterators and Circulators

In order to sequentially access mesh elements pmp::SurfaceMesh provides iterators for each element type:

- pmp::SurfaceMesh::VertexIterator

- pmp::SurfaceMesh::HalfedgeIterator

- pmp::SurfaceMesh::EdgeIterator

- pmp::SurfaceMesh::FaceIterator

Similar to iterators, pmp::SurfaceMesh also provides circulators for the ordered enumeration of all incident vertices, halfedges, or faces around a given face or vertex. The example below demonstrates the use of iterators and circulators for computing the mean valence of a mesh.

\snippet iterators.cpp iterators

Dynamic Properties

Attaching additional attributes to mesh elements is important for many applications. pmp::SurfaceMesh supports properties by means of synchronized arrays that can be (de-)allocated dynamically at run-time. Property arrays are also used internally, e.g., to store vertex coordinates. The example program below shows how to access vertex coordinates through the pre-defined point property.

\snippet barycenter.cpp barycenter

The dynamic (de-)allocation of properties at run-time is managed by a set of four different functions.

-

Add a new property of a specific type for a given element type. Example:

auto vertex_weights = mesh.add_vertex_property<Scalar>("v:weight"); -

Get a handle to an existing property. Example:

auto points = mesh.get_vertex_property<Point>("v:point"); -

Get or add: Return a handle to an existing property if a property of the same type and name exists. If there is no such property, a new one is allocated and its handle is returned. Example:

auto edge_weights = mesh.edge_property<Scalar>("e:weight"); -

Remove a property given its handle:

auto face_colors = mesh.face_property<Color>("f:color"); mesh.remove_face_property(face_colors);

Functions that allocate a new property take an optional default value for the property as a second argument. Example:

mesh.face_property<Color>("f:color", Color(1.0, 0.0, 0.0));

The code excerpt below demonstrates how to allocate, use and remove a custom edge property.

\snippet properties.cpp edge-properties

Connectivity Queries

Commonly used connectivity queries such as retrieving the next halfedge or the target vertex of an halfedge are illustrated below.

Halfedge h;

auto h0 = mesh.next_halfedge(h);

auto h1 = mesh.prev_halfedge(h);

auto h2 = mesh.opposite_halfedge(h);

auto f = mesh.face(h);

auto v0 = mesh.from_vertex(h);

auto v1 = mesh.to_vertex(h);

Topological Operations

pmp::SurfaceMesh also offers higher-level topological operations, such as performing edge flips, edge splits, face splits, or halfedge collapses. The figure below illustrates some of these operations.

The corresponding member functions and their syntax is demonstrated in the pseudo-code below.

Vertex v;

Edge e;

Halfedge h;

Face f;

mesh.split(f, v);

mesh.split(e, v);

mesh.flip(e);

mesh.collapse(h);

When elements are removed from the mesh due to topological changes, the member function pmp::SurfaceMesh::garbage_collection() has to be called in order to ensure the consistency of the data structure.

File I/O

All I/O operations are handled by the pmp::read() and pmp::write() functions. They take a mesh, a file path, and optional pmp::IOFlags as an argument.

We currently support reading and writing several standard file formats: OFF, OBJ, STL. See the reference documentation for the pmp::read() and pmp::write() functions for details on which format supports reading / writing which type of data.

A simple example reading and writing a mesh is shown below.

\snippet io.cpp io